Quality is Key to Being a Player in Lighting Control Specifications. Or is it?

Most B2B manufacturing professionals will tell you that you have to be among the best in terms of quality in order to become a part of a designer’s or owner’s short list. In fact, manufacturers have to achieve a certain “level” of quality (the same or better than competitive brands) or they will likely never be included in specifications.

Most B2B manufacturing professionals will tell you that you have to be among the best in terms of quality in order to become a part of a designer’s or owner’s short list. In fact, manufacturers have to achieve a certain “level” of quality (the same or better than competitive brands) or they will likely never be included in specifications.

But what does “quality” really mean? Furthermore, “quality” about what? The lighting? The control system? The entire building automation system (see our report on Building Automation Systems).

According to the recent 2019 lighting survey conducted by Electrical Contactor Magazine[1], electrical contractors who primarily work on commercial, industrial or institutional projects are most often (88%) asked to discuss lighting quality with owners. In addition, the most often lighting trend owners asked electrical contractors about was the quality of lighting products. 63% of electrical contractors indicated owners were very interested in learning about new trends in the quality of lighting, which was higher than owner’s interest in trends for color tuning, energy information, maintenance alerts or software systems.

Without actual proof of quality and performance, it will be difficult for lighting control manufacturers to be on the list of brand options in the specs or more important, become the “basis of design” for a particular project.

Lighting is Complex

In today’s environment, lighting is becoming increasingly complex. Today’s lighting includes a multitude of sensors that must “talk to” each other and the control system, as well as other components that provide extraordinary control to the lighting. The specification of the lighting controls while often intertwined with the lighting itself should give architects and designers pause when thinking about “quality.” Besides, these controls are often tied directly to energy efficiency, an important topic as sustainability is pursued, and other new trends such as occupant health and wellbeing or IoT. Building owners, for example, think about leveraging lighting systems as “the data network infrastructure for smart building applications.”[2] That is going to require data collection from an even more complex networkof sensors than currentlybeing used.

This gives architects and designers a lot to think about when it comes to determining “quality.” So where it used to be enough to be a part of a firm’s “short list,” today it might be better to be named as the “basis of design” or better yet, be on the brand named in a lighting schedule or required with no substitutions. The best way for manufacturers to become “the brand” required is through building stronger relationships with architects/designers. Knowing what architects need and becoming more informed on the process of specifications can help foster strong relationships.

In fact, because of the complexity in lighting controls today, the road to the short list is wide open for manufacturers of these systems, as well as the lighting devices themselves. As you will see in this report, there is no single manufacturer who dominates the category. Furthermore, because of the acceleration of the category itself, disruption has come to lighting as it has to every other category and industry.

This is the opportunity for new manufacturers or existing manufacturers trying to get a dominant position into the specification, a daunting task to be sure. Architects and designers do not change or review their specs often. In research conducted and published by Architect Magazine titled The Truth About Specification[3], architects find the process of writing and preparing specs somewhat routine and boring. Consequently, many times architects re-use or revise existing specifications. In fact, the research found that only 26% write specs from scratch and 57% end up using specs from a previous project—sometimes using the spec with no changes.

Proven Quality & Performance Helps Manufacturers Win

Getting in the spec is only half the battle. In commercial projects, the process from specification to purchase is complex and involves many influencers—architects, owners, engineers, interior designers, contractors and more. All professionals play a role in whether a specific brand ultimately gets purchased. According to an article in Consulting Specifying Engineer titled “Desiging Lighting Systems and Lighting Controls”[4] there are many factors designers must consider when specifying lighting control systems. Not only do they need to specify quality lighting products and control systems, but they most also balance other factors such as local/national building codes, energy requirements and project objectives. The article goes on to stress the importance of starting with evaluating a client’s needs before diving into product selection and lighting designs. Projects can be unique in size, shape, location and other system requirements that impact the overall project requirements.

Proprietary research conducted by Accountability Information Management, Inc. (AIM), a B2B full-service research and marketing firm indicates that 66% of architects/designers indicated that product durability and long-term performance was the most important benefit when selecting a particular brand of product. This was higher than the design appeal/look where only 32% indicated it was “most important”.

Trying to understand “quality” is a tricky concept. What quality means to one architect or designer may mean something else to another. In addition, a designer has to understand and know their client’s definition of quality. Does quality mean durability or does it mean long term performance? Does it mean reliability or free-from defects?

In fact, AIM’s open-ended research through the years continues to indicate the definition of quality can vary by type of product, project and the professional’s needs. Some words architects and owners have used include: consistent, reliable, dependable, performs/functions as required, long lasting, free from defects, durable and many others.

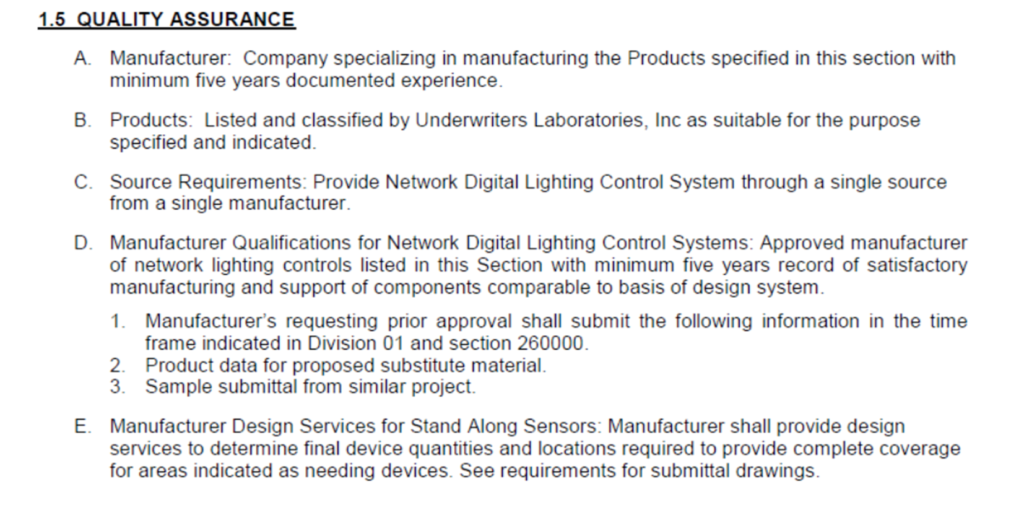

All lighting control specifications will include language requiring the specified products to meet specific industry standards. For example, associations like ASTM, NEMA, IES and others will not only set quality and performance standards but most will test manufacturers products to verify they meet these standards. In addition, lighting control specifications often include quality assurance language or key requirements when it comes to quality. Not only do products need to meet specific building and industry standards but manufacturers must provide proof that the product has performed in similar uses and properties. Architects and designers want manufacturers to have a history of performance for a minimum of 5 years.

Manufacturers must provide architects and other designers with the specific information they need on quality before they will become a part of the architects list of approved brands or become the basis of design. The specific information to provide assurance of a specific product’s quality will depend on a specific project and the designers needs. The manufacturer and their representative must take the time to understand the specific architect’s goals and needs of a particular project. By tracking and evaluating brand placement in project specifications, manufacturers can begin to learn how well their brand is penetrating the design market. In addition, it gives them a way to evaluate their position in relationship to competitors.

Spec Analysis is a Way to Evaluate Manufacturer Success/Failure

A comprehensive Accountability Information Management, Inc. (AIM) Architects’ Brand Preference Study revealed just how competitive the lighting control market is. In this unaided blind brand preference study architects and designers were asked to list their top three brands of lighting control products.

There were over 15 brands or companies mentioned by designers that were “involved” with the specification of these products. Although the list of specific brands no doubt shifts over time, the numerous choices designers have to choose from still holds true. Designers have lots of brand choices when it comes to lighting control products. Or do they?

In our studies, 25% to 35% of the time, the architect is delegating the specification of lighting controls to someone else (the engineer, the developer, the contractor). And today, because of the growing complexity, those people are probably sub-contracting the specification to other specialized professions! How is a manufacturer to navigate this path?

Ultimately, it’s the architect who signs off on the plan, which is why manufacturers must do everything in their power to educate that audience not only on products, but to provide the required assistance in the actual specifications themselves.

How Involved is Involved?

To help manufacturers evaluate their brand position in the marketplace, it is important to first understand more about an architect’s level of involvement when specifying lighting control systems. How much control or influence does the architect or designer have on selecting a particular brand of lighting?

Looking at lighting control products, the degree to which architects are involved in specifying a specific brand or manufacturer can vary. It depends on many project variables and specific project needs. As lighting control systems become more complex and need to be integrated into the entire building automation system, often times the architect delegates these decisions to lighting design professionals or an electrical design expert. In AIM’s Architect’s Brand Preference research, only 48% of the architects surveyed indicated that they were involved in selecting and specifying the brand of lighting control products which is a decrease since an earlier study where 62% were involved. This level of involvement continues to decrease as the complexity of the systems increases.

In addition, 24% indicate they did not have any type of brand preference—an increase from 3% with “no preference” in a previous study. Manufacturers of lighting control seem to be neglecting the architects’ education!

While architects may indicate they have “no preference,” they are, in fact, involved at a certain level in specifying and recommending lighting control products. However, due to the complexity of commercial projects, more architects may delegate the brand selection to lighting “specialist” either lighting designer, electrical designer or “others” in the specification path.

Many design firms today, maintain a list of “approved” brands that meet their performance and quality requirements. If a manufacturer is not on “the list”, the chance of being in a specification are limited. It is becoming increasingly important for manufacturers to expose and educate designers on their product features, benefits, quality standards and services they offer the market.

Becoming a brand on the architect’s preferred list of brands is key to impacting a brand’s position in the specifications. To be on a firm’s list of approved lighting control brands, a manufacturer needs to provide more than just a quality product. They need to have a history of top performance, offer premiere service and local support for their brand. What should lighting control manufacturers do to enhance brand selection and preference? How can manufacturers convert “no preference” or “no awareness” into specifications and recommendations for their brands? These are important questions.

Impacting Brand Specification with the Basis of Design

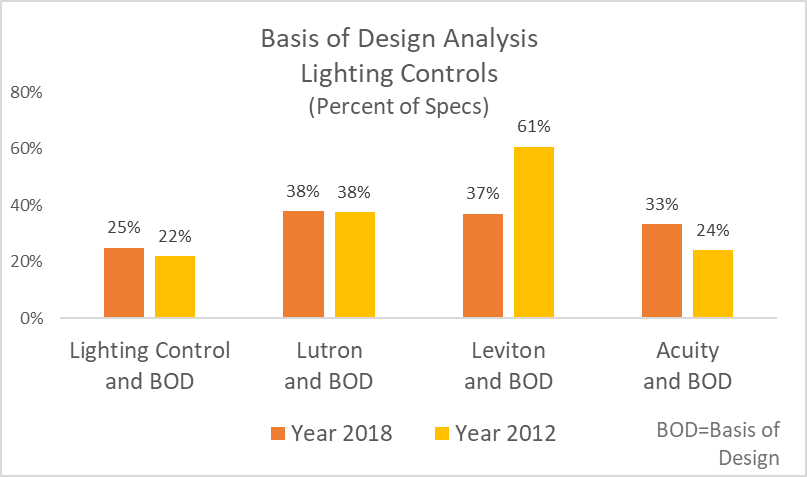

To answer these questions, consider what we know about specifications. The key to gaining ground in specifications is to become part of the “basis of design.”[5] This means that the architect or designer is calling out a specific brand that is used to meet the objectives of the project. To learn more about how often “basis of design” is used in lighting control specs, we used ConstructConnect™, (https://www.constructconnect.com/), an online construction database, to get a better sense of how interior lighting products are specified. By searching the project lighting controls and device specifications for “lighting control projects with Basis of Design,” in specific years, we can see how the specification for “basis of design” and specific brands has changed.

Only 25% of projects in 2018 with a lighting control specification also included a brand as the “basis of design.” However, this has increased slightly since 2012 where “basis of design” was specified in only 22% of the lighting control specifications.

Since there are many national and proven brands that are involved in delivering lighting control products to the market, this type of spec analysis can show manufacturers how often their brand is specified as the “basis of design” and if it has shifted over a specific period of time.

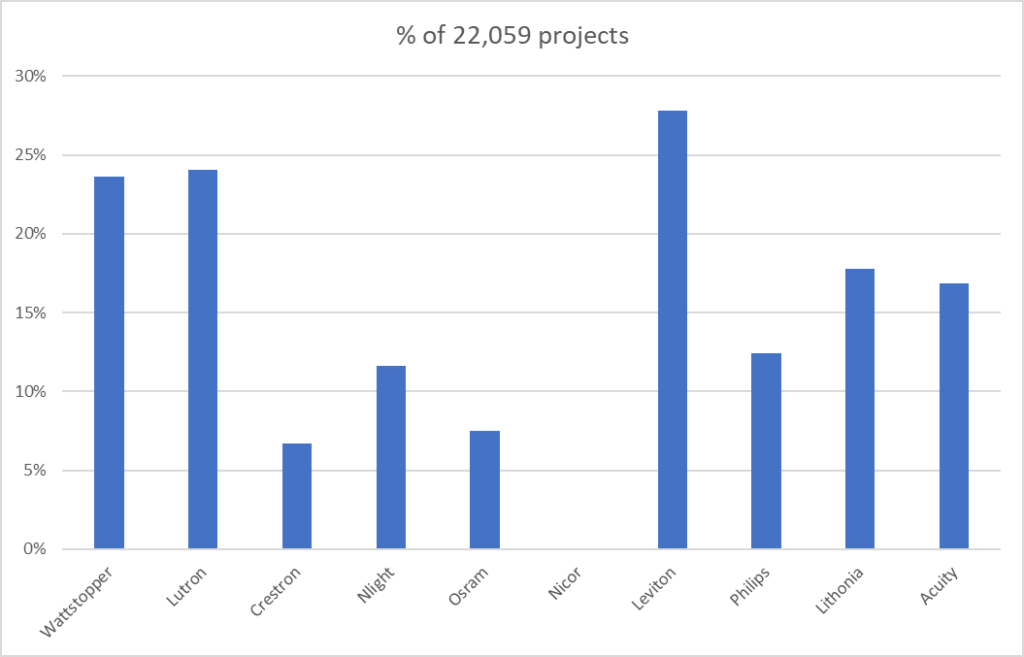

For example, in the current construction projects going on in the U.S. and Canada, 22,059 have “lighting control systems” specifically called out in the specification. Sweets, which is often consulted for manufacturers of products used by architects, only has two manufacturers listed under “lighting control systems.” These two manufacturers hardly showed within this dataset of 22,059.

This lack of listings in a source like Sweets underscores how architects “delegate” such specifications to others as noted earlier. However, what is the real story of manufacturers fighting for this category?

The chart shows a sampling. AIM took a random specification for “lighting control systems” and found specific manufacturers mentioned, and then combined them with our own studies in this category. You can see how “wide open” the category is in terms of a dominant manufacturer: there is none. No single manufacturer has more than 28% of that dataset.

The market is constantly changing and it is important for a manufacturer to continuously review their position in architect’s specifications. While a manufacturer cannot always be sure that they are on a firm’s “preferred” list, they can evaluate how often their brand appears in the specifications and measure how often they are the “basis of the design” or appear in the lighting schedule. If a brand is found in the specifications and certainly is the “basis of design” they are going to be on the list of “preferred” brands.

The same research can be done on the other product categories or on specific brands based on the manufacturer’s needs. AIM can design a spec analysis to meet a client’s objectives and look at a particular brand/manufacturer, by territory, competitors, project type, location or by spec area/schedule. Let us know where your interests are. Thank you.

____________________________

[1] Ear to the Ground Eds Offer Us Their Feedback Lighting , Electrical Contactor Magazine, April 2019. https://www.ecmag.com/section/lighting/ear-ground-ecs-offer-us-their-feedback-lighting

[2]“Top 5 Commercial Lighting Trends in 2019” published by Osram, 3.20.2019.

[3] The Truth About Specification, by John Schneidawind, AIA highlights key findings on an AIA survey of 330 architects on how they select and specify building materials for commercial projects. The article stresses the importance of an architect’s relationship with building product manufacturers and report that 60% of the time the architect already knows which materials an architect is going to use. https://www.architectmagazine.com/aia-architect/aiafeature/the-truth-about-specification_o

[4] Consulting Specifying Engineer Magazine, December 2018; https://www.csemag.com/articles/designing-lighting-systems-lighting-controls

[5]USlegal.com defines it as “Basis of design is a term used in engineering, which typically consists of text paragraphs, preliminary drawings, equipment lists, etc. Well-defined requirements consist of a set of statements that could form the basis of inspection and test acceptance criteria. The basis of design documentation and the specification identify how the design provides the performance and operational requirements of the project and its systems.”