How Manufacturers Make Sure Their Flush Valve Brand Doesn’t Get “Flushed” Out of Designer’s Specs

As water conservation becomes more and more critical to the commercial building industry, designers need to look at more than just cost and aesthetics when selecting a particular brand or type of flush valve.

According to the 2015 EPA WaterSense Fact Sheet [1]there were over 27 million flush valve commercial toilets in existing facilities with an average 500,000 new flushometers/flush valves installed every year. The WaterSense EPA study went on to estimate that there are over 67 billion commercial flushometer/flush valve flushes per year, and that adds up to a lot of water.

By conserving water, building owners can not only be environmentally conscientious but can also save money. More and more architects and engineers need to consider the efficiency and performance of flushometers and flush valves if water conservation is a goal. It is important when specifying a particular brand of flush valve that the architect’s specification stress the importance and requirements for overall performance and water conservation.

So which Flush Valves are being specified? Which ones SHOULD be specified?

Selecting Flushometers or Flush Valves

So often in the construction of new commercial buildings, the up-front cost in relationship to the water conservation goals is the key consideration when selecting and installing a particular brand of flush valve.

While the architect may have specified a particular “brand” based on performance, aesthetics and preference, many times value engineering takes over and an alternative brand is purchased simply because it is cheaper. In the long run, to save a facility time and money, the “true cost” or life-time cost of a flush valve needs should be considered over just the original purchase price.

In a 2018 article published by Construction Canada[2], architects and engineers were encouraged to consider all costs, direct and indirect that would be incurred throughout the life cycle of a product. This would include several factors such as the durability, reliability, ease of installation and product efficiency.

One of the major issues that can impact the life-time cost of a flush valve is the frequency and ease of maintenance. Many times, flush valves are exposed to added vandalism or poor water conditions that increase the long-term cost to maintain the product. According to the WaterSense EPA fact sheet, a flush valve can last up to 20 years but can require parts replacements such as batteries (in the case of electronic) or new diaphragms. Some, like piston flush valves, require less maintenance and deliver more accuracy according to experts in the field. Maintenance will add additional labor costs too.

As far as other selection criteria, the style and look of commercial flush valves or flushometers have not changed too much over the years. Current models may be offered in different finishes or with a manual or electronic option, but the overall design (and functionality) has not changed much. For some types of projects, architects and interior designers may look for flush valves that have a unique look or style. However, the flush valve must still demonstrate superior performance and long-term durability. Manufacturers that can design a unique flush valve design that offers superior performance and durability may just have a way to differentiate their brand from the “others” specified.

One of the best ways for manufacturers to increase their position in this market is to provide architects, designers and engineers with data and “real” examples of their flush valve’s long-term performance and durability by type of building. In a 2019 Accountability Information Management, Inc. (AIM) Market Trends Research Study[3], building professionals indicated that their biggest fear in trying new products was that the product won’t perform or last as long as promised. With actual proof of performance and durability manufacturers have a better chance of being specified and ultimately installed.

Using Spec Analysis Strengthen a Brand’s Market Position

Many manufactures work hard to get their brand in the architect’s specification and to be included in the list of approved brands. For many manufacturers getting a product into the specification can be a difficult task. Architects and designers do not change or review their specs often.

In research conducted and published by Architect Magazine titled The Truth About Specification[4], many times architects re-use or revise existing specifications.

AIM’s own Brand Preference Study revealed just how competitive the flush valve market is. In this unaided blind brand preference study, architects and designers were asked to list their top three brands of flush valve/flushometer products.

There were over 10 brands or companies mentioned by architects that were “involved” with the specification of these products. Although the list of specific brands has no doubt shifted over time, the numerous choices designers have to choose from still holds true. Designers have lots of brand choices when it comes to flush valve products. In fact, the recent search of specs for flush valves there were often at least 5 brands specified and contractors could basically select any brand that complied with the performance requirements outlined in the specification or in the drawings.

To help manufacturers evaluate their brand position in the marketplace, it is important to first understand more about an architect’s level of involvement when specifying flush valve products. How much control or influence does the architect or designer have on selecting a particular brand of flush valve.

To help manufacturers evaluate their brand position in the marketplace, it is important to first understand more about an architect’s level of involvement when specifying flush valve products. How much control or influence does the architect or designer have on selecting a particular brand of flush valve.

Influence Matters

Looking at flush valves, the architects’ involvement in specifying a specific brand or manufacturer can vary based on the project type and impact on the overall project. In AIM’s Architect’s Brand Preference research, 45% of the architects surveyed indicated that they were involved in selecting and specifying the brand of flush valve. However, of those that were involved, 31% indicated they did not have a brand preference.

This was a major increase since previous research which indicated only 3% had no brand preference. Seemingly, brand in flushometers is meaning less and less.

Could this be that the specification of flush valves doesn’t matter to the architect or is this type of specification and decision on brand delegated to other professionals? Or possibly, the architect really doesn’t perceive any differences among brand?

While architects may indicate they have “no preference,” they are, in fact, involved in specifying and recommending commercial flush valves. The architect will weigh in on the type of look or performance they want achieve. However, due to the increasingly complexity of commercial projects (i.e., IoT and other trends), architects may delegate the brand selection to “others” in the specification path.

Many design firms today maintain a list of “approved” brands that have met specific performance and quality requirements. If a manufacturer is not on “the list”, the chance of being in a specification are limited. It is becoming increasingly important for manufacturers to expose and educate architects on their product features, benefits and other services they offer the market.

Becoming a brand on the architect’s preferred list of brands is key to impacting a brand’s position in the specifications. To be on a firm’s list of approved flush valves, a manufacturer needs to provide more than just a quality product. They need to have a history of top performance, offer premiere service and local support for their brand. What can flush valve manufacturers do to enhance brand selection and preference? How can manufacturers convert “no preference” answers into specifications and recommendations for their brands? These are important questions.

Brand

In one of AIM’s research reports – What is a Brand – we argued that “Architects are like ranchers when it comes to managing brands that they specify. While the architect may specify a variety of different manufacturers’ brands (beef), it’s the firm’s name on the door that owner hires — not the manufacturer(s). The architectural firm itself becomes the “brand” and the assurance that the products in that specification offer quality and reliability.”

Products like flush valves have been around a long time, and specific brands have established themselves within these categories. However, the Internet has changed this, as has mergers and acquisitions of companies. One thing is certain: the installed base is where the battle for brand dominance takes place. New companies entering the market know this; they go after high-valued projects to break through and establish performance.

The measurement of who wins and loses is always in the specifications themselves. When a market like flush valves who has seen the same names year over year start seeing new entrants on the specifications, that is the signal that the game is changing. Architects are driven people – who seek knowledge to help their clients build the best building that they can build. That thirst for knowledge is also a thirst for creativity – solutions that not just sound good, but actually deliver on performance. This is why the “Basis of Design” becomes a critical factor in understanding how to impact market penetration.

Impacting Brand Specification with the Basis of Design

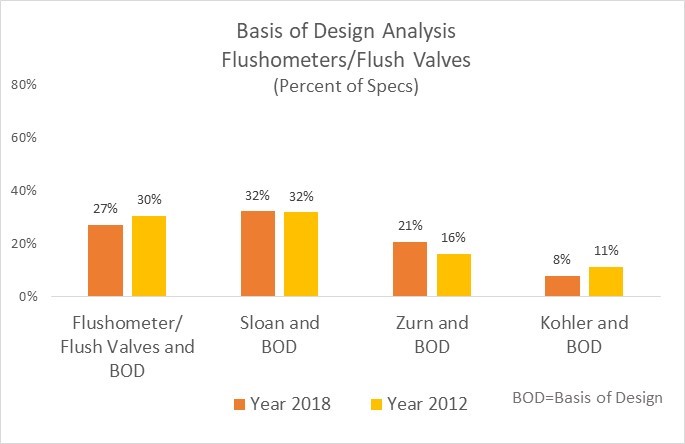

Consider what we know about specifications. The key to gaining ground in specifications is to become part of the “basis of design.”[5] This means that the architect or designer is calling out a specific brand that is used to meet the objectives of the project. To learn more about how often “basis of design” is used in flushometer/flush valve specs, we used ConstructConnect™, (https://www.constructconnect.com/), an online construction database, to get a better sense of how flush valves are specified. By searching the projects plumbing specifications for “flushometer or flush valve with Basis of Design,” in specific years, we can see how the specification for “basis of design” and specific brands has changed.

Only 27% of projects in 2018 with a flush valve specification also included a brand as the “basis of design.” In fact, this has decreased since 2012 where “basis of design” was specified in 30% of the flush valve specifications.

Think about that: almost 75% of projects are non-brand specific! This is the signal that it is a commodity marketplace – and can be available for a new or established player to gain market share.

AIM’s analysis also indicated that while the number of projects that have a “basis of design” spec is fairly low, there are specific brands that consistently appear as the basis of design.

Since there are many brands that are involved in delivering flush valves to the market, this type of spec analysis can show manufacturers how often their brand is specified as the “basis of design” and if it has shifted over a specific period of time.

Ultimately, the owner or facility will have control of the brand that is purchased but contractors, architects and engineers all have influence. Recent research we conducted suggests 6 to 10 people are involved in a purchasing decision!

In another proprietary piece of research conducted by AIM, we saw – for the first time – where the leader in this category was displaced in architectural specifications by another brand! The conclusion is obvious: they are fighting harder!

Since the market is constantly changing as new and existing manufacturers introduce new products to the it, what is important is for a manufacturer to continuously review their position in the project specifications. While a manufacturer cannot always be sure that they are on a firm’s “preferred” list, they can evaluate how often their brand appears in the specifications and measure how often they are the “basis of the design” or appear in the project schedules.

If a brand is found in the specifications and is the “basis of design”, they certainly are going to be on the list of “preferred” brands. Recent analysis of the flush valve specs also indicates that the “basis of design” brand may not even be listed in the spec, but can only be found on the drawings.

To avoid being replaced, flush valve manufacturers may want to strive to be specified as the brand with “no substitutions”.

The same research can be done on the other product categories or on specific brands based on the manufacturer’s needs. AIM can design a spec analysis to meet a client’s objectives and look at a particular brand/manufacturer, by territory, competitors, project type, location or by spec area/schedule. Let us know where your interests are. Thank you.

______________________________

[1] EPA WaterSense Flushometer-Valve Toilet Fact Sheet (EPA-832-F-13-003) December 2015 https://www.epa.gov/watersense/commercial-toilets

[2] Construction Canada, “Consider Lifetime Cost When Specifying Commercial Plumbing Products”,

December 4, 2018,

[3] 2019 Market Trends Study on Product Selection, October 2019, On-line survey with 170 architects, designers and facility professionals. Open-ended comments indicated over 50% of respondents feared a new product would not perform or last as long as promised.

[4] The Truth About Specification, by John Schneidawind, AIA highlights key findings on an AIA survey of 330 architects on how they select and specify building materials for commercial projects. The article stresses the importance of an architect’s relationship with building product manufacturers and report that 60% of the time the architect already knows which materials an architect is going to use. https://www.architectmagazine.com/aia-architect/aiafeature/the-truth-about-specification_o

[5]USlegal.com defines it as “Basis of design is a term used in engineering, which typically consists of text paragraphs, preliminary drawings, equipment lists, etc. Well-defined requirements consist of a set of statements that could form the basis of inspection and test acceptance criteria. The basis of design documentation and the specification identify how the design provides the performance and operational requirements of the project and its systems.”